This article was originally featured here.

By Dickon Pinner, Senior Partner, McKinsey & Co.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused us to reimagine many fundamental aspects of business and society faster than thought possible just six months ago, in ways that could help accelerate our response to climate change. This was perhaps the most conclusive takeaway from our eighth annual Global Sustainability Summit, the first time our event was hosted virtually due to the quarantine and travel restrictions we are now all too familiar with.

Across four virtual sessions this summer, McKinsey brought together more than 600 corporate executives, nonprofit leaders, government officials, and scientists to discuss how to address climate change in a post-pandemic world, what a climate-resilient future might look like, what the most promising innovations for decarbonization are, and how to achieve a 1.5-degree Celsius pathway. Our goal: promoting an orderly transition to a low-carbon, sustainable economy.

In this ever-changing global context, business leaders and policy makers will need to understand that climate change is fundamentally a risk management problem, one that requires thoughtful management, prudent investment, and technological and corporate innovation. Below are some of the key lessons we heard from leaders who spoke at the Summit, lessons that business leaders and policy makers would be wise to keep in mind when collaborating on solutions to manage climate risk.

1. We should view climate change as a risk multiplier of “S” and “G”

As our Summit commenced, it became clear that any conversation about climate change would be inseparable from the sweeping social and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the specter of coronavirus is everywhere, nothing has changed about the urgency of climate change. A focused response to climate risk is critical to simultaneously accelerate the economic recovery from the pandemic and to strengthen our long-term economic and environmental resilience.

Climate risk and pandemics may present many of the same physical shocks to our economy, but their immediate social consequences have been different. Today, any organization’s response to climate change—or the E in their ESG strategy—must be defined alongside a rapidly shifting social context (the S) in light of the pandemic. Indeed, climate change will be a significant risk multiplier of both Social and Governance, exposing the frailties in both.

“Long gone are the days where we thought that human health and planetary health were completely separate issues. Long gone are the days where economic stability and climate stability were separate issues,” said Christiana Figueres, co-founder of Global Optimism, in our Summit’s final installment about achieving a 1.5-degree pathway. “We are now finally understanding that all of this is interlinked.”

It will be the social and psychological effects of the pandemic that may propel the push toward a more sustainable future, especially among Generation Z and young Millennials, said Larry Fink, chairman and CEO of BlackRock, during the Summit’s opening session.

“They have a whole different experience today than what I had,” Fink said of the generation who has experienced 9/11, the Great Recession, and recent social upheavals. “I believe [the COVID-19 pandemic] is going to be one of those transformations of psyche that’s going to emphasize and accelerate the world’s desire to quickly adapt to a more sustainable world.”

Perhaps Spencer Glendon, an economist with Woods Hole Research Center and founder of Probable Futures, put an even finer point on it: “If you’re in a conversation about dealing with climate change and no one is under the age of 50,” he said, “the chances of you reaching a good conclusion are extremely low.”

2. We must shatter illusions of stability

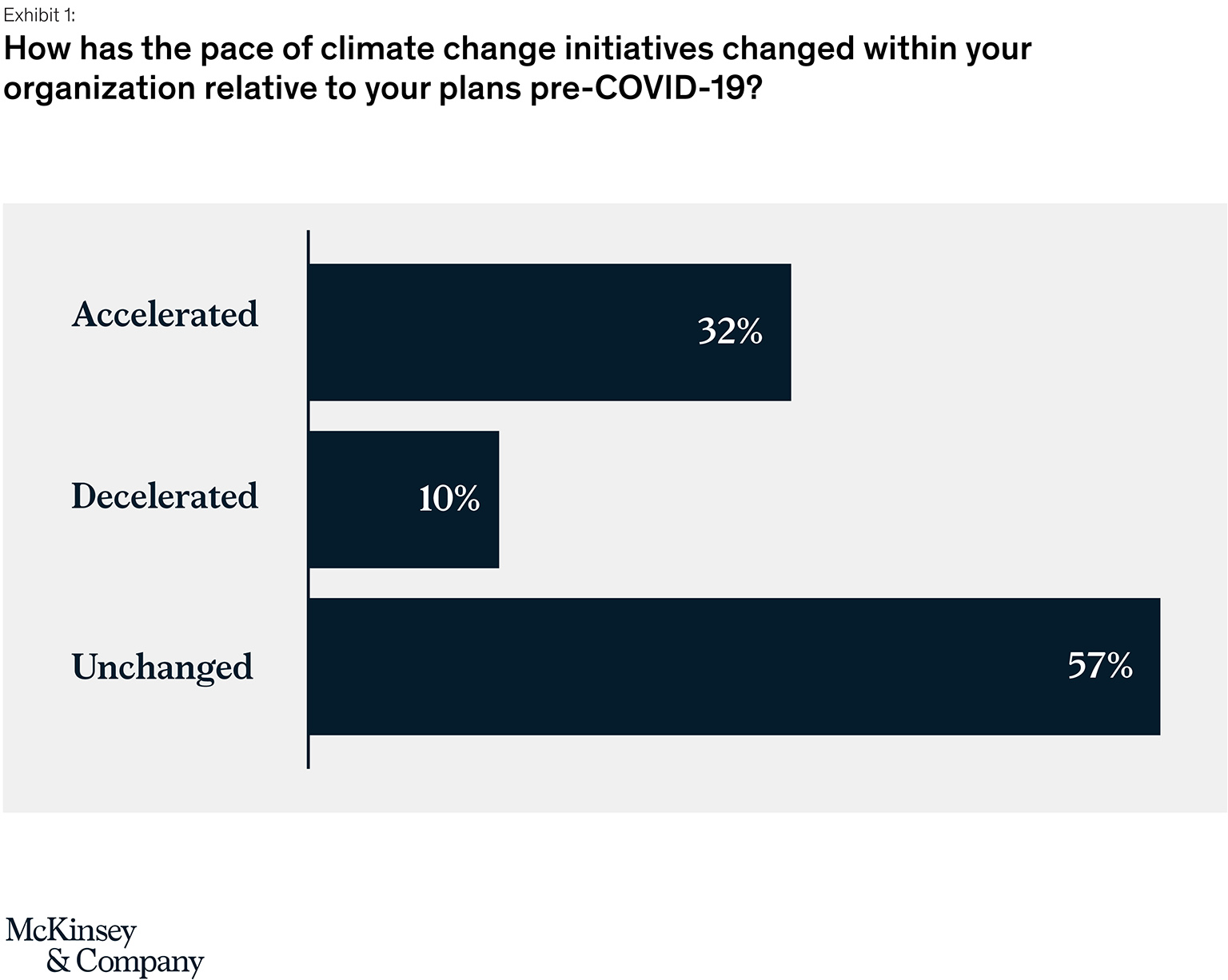

While many attendees agreed that COVID-19 could accelerate their company’s response to climate risk (see Exhibit 1), our panelists also pointed out a number of systemic barriers preventing us from making substantive progress on the mitigation front. One of those barriers is that we have entire economies, markets, and infrastructure built on the faulty premise that Earth’s climate will remain relatively stable.

“Much of the world we live in today—the buildings we live in, what we eat, where we work—all relies on the assumption of a stable climate,” said Mekala Krishnan, a senior fellow at the McKinsey Global Institute. “As climate change intensifies, that assumption may simply no longer hold true.”

Climate risk is inherently unstable. It is both increasing and non-stationary—its effects reveal themselves over cumulative increases that could have substantial knock-on effects for other industries and sectors. Organizations must bake that volatility into their risk management models. For instance, few nations today have their own country-specific climate risk framework, an oversight that ignores the climate change is local and spatial. Even the financial models that corporations and governments use to guide their investment decisions are based on a misguided sense of stability.

“Financial models are almost entirely built on the last 50 years, and in the last 50 years nothing happened. We had one bout of inflation and one real financial crisis—two if you count the Asian financial crisis,” Spencer Glendon, an economist with Woods Hole Research Center and founder of Probable Futures, said. “Data sets that are embodied in those models are only offering us narrow outcomes.”

3. “Climate risk = investment risk”

These narrow outcomes are preventing investors from understanding the full scope of the risks they face when allocating capital. It’s a bias that results in too much capital going into maintaining existing assets and not nearly enough going into risk reduction or innovation.

Mark Carney, United Nations Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance, highlighted that one way businesses can address this is to adopt consistent and reliable disclosures as a way to provide investors with the information they need to make smarter long-term capital allocation decisions.

“It’s not just about disclosing the current carbon footprints of a given company—it’s about where they are headed tomorrow, how they are governed, and how the company itself looks at the sensitivities around the climate transition,” Carney said. “Providers of capital—whether they are banks or asset managers—should also be revealing to clients how their portfolios align with the transition to net zero. If providers of capital have to answer these questions themselves, they will be more likely to ask users of capital for more information. It’s a self-reinforcing cycle that helps adjusts capital allocation to where the real opportunities are.”

Achieving this self-reinforcing cycle will require businesses to build out their climate risk capacity just like they would build any other business capacity, such as operations or marketing. It requires executives to consider the talent and teams at their disposal, their replicable business processes, and the technology platforms they have to measure, track, and engage suppliers, said Kathleen McLaughlin, executive vice president and chief sustainability officer at Walmart.

“This is not CSR and it’s not philanthropy,” she said. “It’s framing it as the way you run a business.”

4. Governments and corporations must work together, particularly in a post-pandemic world

“I’ve been working on adaptation now for probably 20 years, and it’s so common to hear people say, ‘Well, it’s not my job. I don’t have the mandate,’” Christina Chan, head of the World Resources Institute’s climate resilience practice, said. “Building resiliency into everyday business has to be part of what everyone does.”

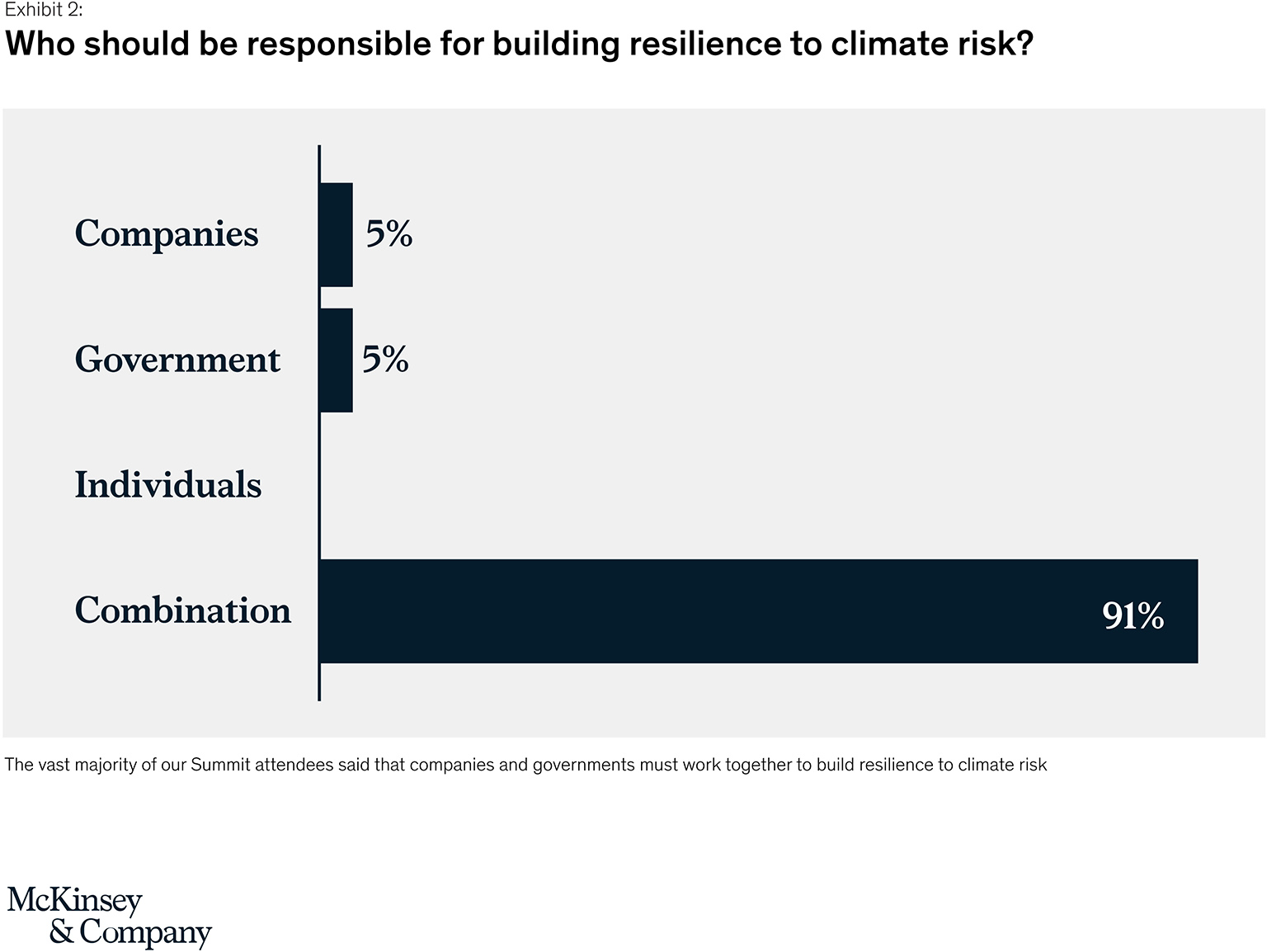

Part of creating an environment that empowers leaders across all sectors to take a more active role in addressing climate risk will involve more active collaboration from companies, governments, and individuals. While each is responsible for their own unique climate risk response, each has a unique role to play in helping manage the collective climate risk. Collaboration between the public and private sector will prove especially important to calibrate.

“It’s very difficult for an individual company or sector to fund R&D today that may only produce results in 10, 20 years from now,” Victoria Scotti, chairperson of public sector solution at Swiss Re, said in the Summit’s second installment on a climate-resilient future. “I think public-private partnerships can essentially mitigate the risk that otherwise is difficult for private capital to take on.”

Certainly the public sector will play a significant role developing incentives for more adaptive decision making and creating disincentives for maladaptation in the private sector, according to Chan. But during the next major climate decision-making junctures, such as COP26 next year, our panelists believe it will be the private sector that will play an outsize role catalyzing government action.

“Most people will not know that the Paris Agreement was adopted in large part because there was a very determined private sector mobilization prior to the Paris Agreement—businesses already engaging in their own decarbonization and encouraging their respective governments to adopt an ambitious agreement,” said Figueres, who helped negotiate the agreement in 2015.

While much of that private sector mobilization was eclipsed by reporting about the multilateral success of the treaty, the private sector’s role in defining next year’s climate negotiations will be even more pronounced than it was in 2015.

“The real economy will inform the government’s response to COP26,” she concluded.

5. Innovate aggressively—and not just technology

Our panelists agreed that to respond effectively to the compounding effects of climate change, companies must continue to innovate. But much of that innovation won’t be technological.

“We have seen solar and wind get to scale and get to cost-competitiveness. Similarly, electric vehicles are on a path to competitiveness within the next few years,” Kimberly Henderson, a partner in our Washington office, said. “We need some innovations that aren’t technologies, but market innovations.”

Kimberly went on to include as examples business model and market innovations that make recycling economically viable, getting new technologies like carbon capture and hydrogen electrolysis down the cost curve, and reimagining how players get compensated.

“It’s about innovation leading us to the point where we do not have to choose between doing right for our planet and doing right for the economy,” said Ira Ehrenpreis, founder and managing partner at DBL Partners. “It is about scale leading to cost reduction. And not many would have predicted in 2000, when you had LEDs at a hundred dollars a lumen, that today we’d be at a penny at lumen. Or in the last 10 years we’d have solar PVs reduced in price by 90 percent.”

Coronavirus has already accelerated some of the momentum in these areas, especially around banks requiring disclosures, climate stress tests for capital borrowers, and tools to assess climate risk. But to successfully chart a reliable pathway to achieve a 1.5-degree Celsius limit to global warming, we will have to err on the side of innovation, collaboration, and openness to change.

“I think, in all of these issues, we can’t be afraid of change,” Jim Fitterling, chairman and CEO of Dow, concluded. “I think we’ve got to be a little bit more afraid of not changing.”

__________

Dickon Pinner leads McKinsey’s Sustainability Practice globally, where he helps transform companies’ product, service, and asset portfolios to capture the opportunities and mitigate the risks posed by climate change and other sustainability issues.

Dickon Pinner leads McKinsey’s Sustainability Practice globally, where he helps transform companies’ product, service, and asset portfolios to capture the opportunities and mitigate the risks posed by climate change and other sustainability issues.