By Amy Meyer, Associate, WRI Center for Sustainable Business

WRI will host a webinar on this topic on June 30, 2021. Register here to attend.

For the past few years, and especially over the past few months, the bar for corporate sustainability leadership has been raised. While an increasing number of companies are setting targets to reduce their emissions and to protect the global commons (air, water, land, biodiversity and ocean), it is increasingly recognized that these voluntary commitments are not enough. Without ambitious public policy, the U.S. will have no chance of meeting its commitments under the Paris Agreement and keep the world on a 1.5-degree pathway.

WRI has been actively calling on companies to incorporate climate policy leadership into their sustainability strategies. This call has been further echoed by our NGO peers, investors, activists, students and even by companies themselves. However, as a proud “do-tank”, we were compelled to go beyond why companies should do this and what it looks like, to also tackle the how.

The business case for practicing corporate climate advocacy is strong, so why are we still seeing misalignment between companies’ sustainability and political engagement strategies?

A new WRI working paper provides an answer.

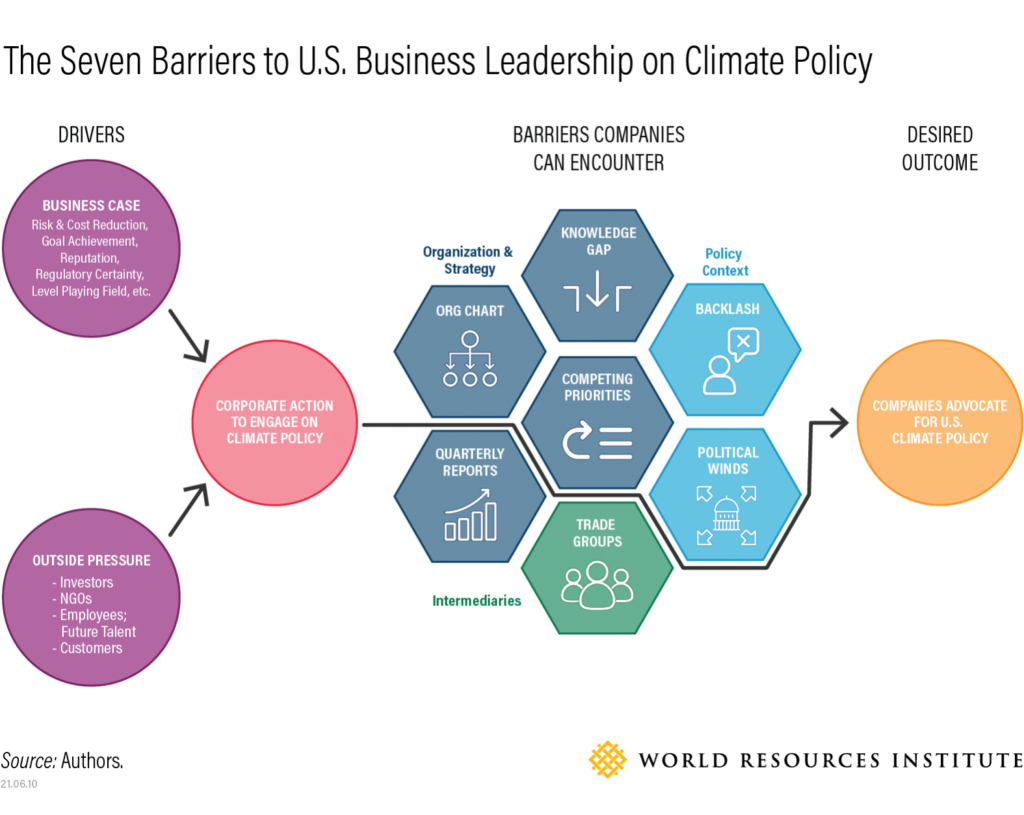

We identify seven key barriers that companies must navigate to be strong and effective climate policy advocates.

The Barriers

These barriers fall into three categories, as shown in the image above.

1. Organization and Strategy Barriers

Four barriers relate to internal dynamics within a company and are, mostly, subject to the decision-making of the CEO and the board of directors. We’ve termed these “Organization and Strategy” barriers, and are as follows:

Org Chart: Though corporate structure varies from company to company, traditionally staff have not been organized in a manner that promotes collaboration or shared objectives between the sustainability and government affairs teams. Without a clear directive from the CEO to incorporate climate goals into lobbying activities, most staff on either team are unaware that their efforts often work at cross-purposes. Our research revealed that it is common for staff in sustainability departments to be unable to name a single colleague working on state or federal policy engagement, which further relays this incongruency.

Competing Priorities: We found that companies often regard their top advocacy priorities as a set of 1-3 topics; climate change rarely makes the cut. Many companies see climate policy as outside their “swim lane” if they are not major emitters, energy-intensive users, or clean energy producers. Instead, they prioritize their advocacy efforts around other issues (e.g., tax or trade policy) considered to be more material. A sense of having limited political capital exacerbates this dynamic.

Knowledge Gap: It is no small feat to remain fully knowledgeable on the science of climate change, US federal policymaking procedures, and the implications on individual business or industry sectors. Translating that into a nuanced understanding of the costs of inaction requires significant investment, and teams of experts dedicated to understanding these ever-evolving dynamics are needed. Most companies have not yet invested the necessary time and resources to “get smart” on climate policy.

Quarterly Reports: Short-term profit often prevails over long-term public (and private) interests. The pressure of quarterly reporting, driven by legal requirements and a model of shareholder primacy, disadvantages long-term investments in climate change. Companies too often have short-term motivations, which may lead them to act against the company’s, and society’s, long-term interests. This can be exacerbated by a system that often rewards CEOs based on stock-performance and market success, offering massive financial incentives for corporate leaders to maximize near-term outcomes.

2. Trade or Industry Associations

Looking outside the company itself, another major barrier identified is the role of lobbying intermediaries. In the U.S., the biggest conduits for political influence are trade or industry associations. WRI has written extensively on the impact of these organizations on climate policy, found here, here, and here.

Trade associations wield immense influence with policymakers and often have massive budgets on hand dedicated to lobbying Congress. These groups have historically gravitated toward representing the industries with the most to lose, and for multi-sector associations this means favoring the interests of some sectors over others on certain topics. Although many companies have begun calling for national climate action, their trade associations may be actively undermining their interests in favor of heavy emitters.

3. Policy Context

Finally, there are those barriers that fall outside of individual companies’ control, namely the country’s political environment. We identify the following two barriers:

Backlash: When taking a political stand of any sort, companies risk facing backlash from numerous stakeholders, including politicians, consumers, customers, employees and even the board of directors. Though research shows the public’s attitude towards climate action is trending more in favor, the perceived risks of lobbying for climate action can outweigh perceived benefits.

Political Winds: Major climate policy was absent from the congressional agenda for the decade prior to the 2020 election. Without large-scale climate legislation to rally behind, many companies are unclear on what role they should play.

Call to Action

We are not making excuses for inaction. A critical source of these findings was speaking with companies that have been relatively successful in lobbying for climate policy and learning about their journeys and the challenges they faced. There are leaders in this space and important lessons learned.

For those companies just starting to look at the impact of their political influence on the climate crisis, or for those that have been trying but struggling to align their actions, we encourage you to read our full paper. Actually, no matter who you are, please give it a look! Through our own experience and the experience of others, we have collected and distilled a checklist of actions companies can take to begin overcoming each of the barriers. Whether it’s realigning incentives, auditing trade associations, or partnering with strategic corporate peers, there are many options to address these challenges.

Getting Started

Here are three actions CEOs can take today to advance their company’s climate strategy and empower key corporate actors to overcome the seven barriers:

- Send a climate memo. Address it to your company’s chief sustainability officer and vice president of government affairs. Connect the company’s sustainability goals with its lobbying priorities and direct the two teams to collaborate.

- Include the climate ask. When you sit down with your trade association’s leadership for its annual meeting, ask how the association is representing the company’s climate interests. Make clear to the trade association’s leadership that climate policy is a critical issue to the company.

- Tell your climate stories. Describe how policy action, or inaction, will affect the company. Show connections to the interests of your investors, customers, communities, and employees (current and future).

Voluntary actions to reduce emissions are important, but only public policy can deliver reductions at the speed and scale needed to limit the worst impacts of climate change. As a result, climate policy advocacy is an essential element of corporate sustainability leadership.

This article originally appeared on the WRI website and is reprinted with permission. For related resources, visit WRI’s Corporate Climate Policy Leadership page.