By Michael A. Levi & Lindsay Iversen, Council on Foreign Relations

Introduction

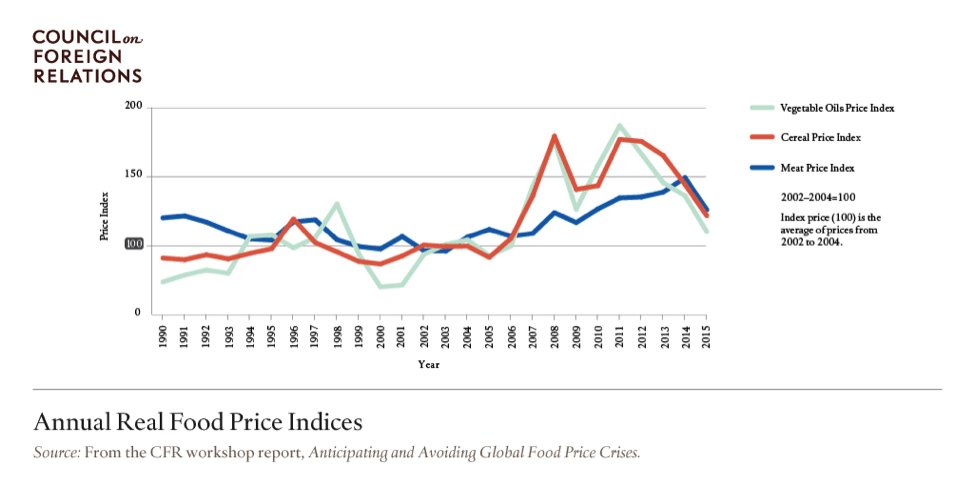

Sudden, sharp increases in food prices have occurred more frequently in the last decade than in the previous thirty years, leading analysts to wonder whether a generation of relative stability has come to an end. The answer will have potentially serious consequences for market participants worldwide, from poor consumers to agricultural businesses. Government interventions intended to prevent or moderate spikes can often fail and sometimes even exacerbate increases in international prices. Not only can that complicate business’s efforts to cope with spiking prices, it can also wreak havoc on consumers’ ability to sustain their livelihoods (or, in extreme circumstances, their lives).

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), an independent, non-partisan think tank, convened a group of twenty experts from academia, government, and business to debate why food price crises have occurred more frequently in recent years, whether that phenomenon is likely to continue, and what, if anything, governments and others can do to prevent such events. The discussion was not for attribution and did not require a consensus; opinions voiced by participants were their own and did not represent other attendees or CFR. The full report is available here.

Looking Forward

Workshop participants expected the recent volatility in agricultural commodity prices to remain a feature of markets for the foreseeable future. Most expected another crisis along the lines of the 2008 price spike within the next five years; all agreed that such a crisis was likely in the next decade. Population growth is steadily increasing the global demand for food, while rising non-food uses for crops are likewise putting upward pressure on prices. And droughts and other weather anomalies – common triggers for food price crises – are likely to become more frequent as climate change takes hold in the years to come.

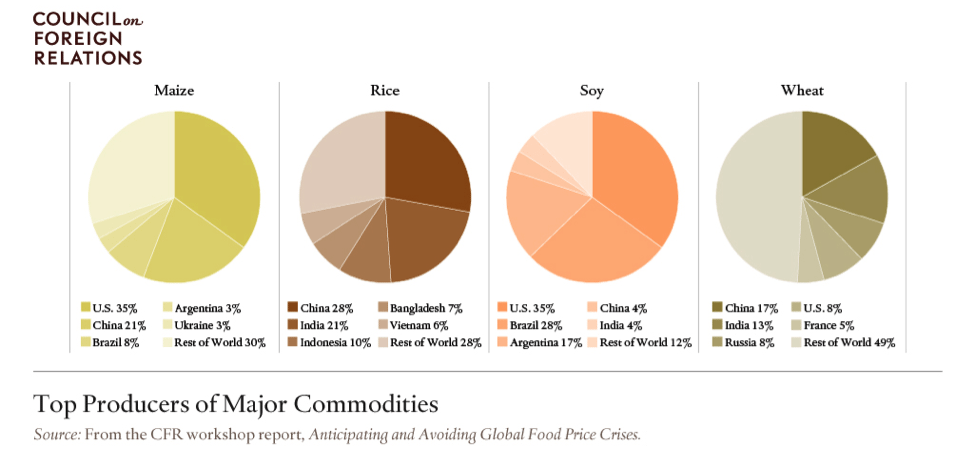

Though most food is grown and consumed locally, the globalization of agriculture is rising: some twenty percent of production now crosses an international border. Most production for export, however, is concentrated in a small number of countries, making global markets vulnerable to shocks in these major producers.

Technological developments have dramatically increased yields in these countries (mainly though not exclusively in the developed world), but the benefits of improved seeds and other innovations have yet to reach many countries with significant agricultural potential, particularly in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa. Improving crop productivity and resilience in those areas will be important to ensuring sufficient and steady food supply in the years to come.

Technological developments have dramatically increased yields in these countries (mainly though not exclusively in the developed world), but the benefits of improved seeds and other innovations have yet to reach many countries with significant agricultural potential, particularly in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa. Improving crop productivity and resilience in those areas will be important to ensuring sufficient and steady food supply in the years to come.

Toolkit is Sparse

Governments often try to guard against price spikes by maintaining stockpiles of critical commodities. This strategy makes intuitive sense: it enables governments to absorb excess stocks at times of low prices and release them when prices are high, easing economic difficulties for producers and consumers at different points in the cycle. The problem is, the strategy rarely works.

Stockpiles have a poor record when it comes to actually preventing or mitigating price spikes. Governments often lack the technical capacity to manage them well, and imperfect information on what other countries or market players are likely to do makes it extremely difficult to time the building and release of stocks in an optimal fashion. Workshop participants unanimously agreed that, under likely conditions of information and governance, stockpiles could never be a reliable tool for countering volatility.

When crises do hit, governments can be tempted to put in place export bans or other restrictions on trade to try to keep food close to home. Though these policies offer a degree of protection to local consumers, they are morally and economically double-edged. By limiting international supply, export bans can exacerbate crises in global prices, slamming poor consumers in other countries even as people at home are shielded from the worst.

Unfortunately, participants reluctantly agreed, there is little appetite to change international trading rules to prevent such actions. There are currently few restrictions on when and whether governments can put in place export bans. In recent negotiations at the World Trade Organization, the only proposed limit that received even tepid support was a requirement that countries provide advance notice before implementing export bans. This proposal has not been adopted.

What Can Be Done

The workshop participants were not, however, without hope that steps could be taken to prevent or mitigate food price crises. A full list of their constructive proposals can be found here; highlights include:

- Accelerate research and development and technology transfer in agriculture, particularly in biotech and other technologies that would improve farmers’ ability to adapt to changing climatic and market conditions;

- Encourage large exporting countries to undertake formal commitments to maintain open exports during future price crises to help minimize price distortions;

- Pursue a broad, international agreement requiring countries to provide prior notification before implementing export bans or equivalent trade restrictions; and

- Use the UN climate agreement reached in Paris, based on national pledges of action, as a template for international collaboration on rationalizing food stockpiling and export bans.